ABSTRACT

Purpose

Emergency medicine is the first-contact medical specialty that deals with the initial management of emergency conditions. Emergency Medical Services (EMS) frequently encounters urgent situations in oncology. The aim of this paper is to present the oncological reasons for such interventions by emergency response teams, with the goal of understanding the needs of oncology patients, so that, their healthcare in the field of emergency medicine can be improved.

Methods

The study utilized data from patient protocols from field interventions conducted by the EMS of Community Health Center “Dr. Milorad Vlajkovic” Barajevo (HCB), covering the period from 00:00:00 on January 1, 2023, to 23:59:59 on December 31,2023. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 21.

Results

During the observed period, EMS HCB conducted a total of 3,345 field interventions. Of the total number of patients, 175 (5.23%) had a diagnosis or diagnoses of some malignant disease. Among these patients, 69 (39.4%) were male and 106 (60.6%) were female. The minimum age was 37; the maximum was 89, with a mean age of 65.67 and a median of 66 years. The most common individual diagnosis was C50, and the most frequently administered therapy was dexamethasone.

Conclusion

The number of people suffering from malignant diseases is increasing. Thus, increasing the amount of resources dedicated to the emergency care of oncological patients and the provision of palliative care is essential. Furthermore, a comprehensive study of the needs of oncology patients in the field of emergency medicine is also necessary.

INTRODUCTION

Malignant diseases are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), nearly 10 million people died from malignant diseases in 2020, meaning that one in every six deaths was associated with malignancies.[1] The most common malignancies, according to WHO, are breast cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer and prostate cancer. In Serbia, malignant diseases are the second most frequent cause of morbidity and mortality,[2,3] with lung cancer being the most common malignancy in terms of both morbidity and mortality.[4] Globally, it is projected that, based on data from 2017-2019, approximately 40.5% of people will be diagnosed with cancer at some point in their lives.[5] The same source estimates that in 2024, nearly 15,000 children and adolescents will develop cancer, with around 1,500 expected to die from it. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, which is a part of the WHO, it is anticipated that by 2045, more than 36 million people will be living with cancer.[6] Emergency Medicine (EM) is the first-contact specialty that deals with the initial management of emergency conditions. EMS frequently encounters urgent situations in oncology.[7]

The aim of this research is to present the oncological reasons for the interventions performed by the field teams of the EMS of HCB Additional objectives include the showcasing of cancer-related treatments administered by the EMS teams and the referral of oncology patients to higher levels of the healthcare system. This research aims to comprehensively assess the needs of oncology patients requiring EMS interventions, with the goal of improving prehospital care conditions for such patients. Ultimately, recognizing urgent situations enhances the quality of life for oncological patients, reduces mortality and, extends survival.[8]

Cancer can, be conditionally classified into Early-Onset Cancer (EOC), which occurs before the age of 50 and Late-Onset cancer (LOS), which occurs at age 50 or later.[9]

METHODS

The study utilized data from patient protocols from field interventions conducted by the EMS HCB, covering the period from 00:00:00 on January 1, 2023, to 23:59:59 on December 31, 2023. Data from these protocols included information on gender, age, the month of the year, diagnoses, therapies administered during the EMS visits, as well as information on patients’ referrals to higher levels of the healthcare system.

Patients were categorized into age groups as follows: 0 years (y), 1 to 4 y, 5 to 14 y, 15 to 24 y, 25 to 34 y, 35 to 54 y, 55 to 64 y and 65 y and older. This age categorization, adapted from WHO, was modified for the purposes of this study.[10] The age of patients was determined by subtracting the year of birth from 2023. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 21.

The data used were processed in accordance with good research practices, without the use of names, surnames, identification numbers, or any other data not mentioned in the Methods section. Approval for the use and analysis of patient protocols and data was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the HCB, filed under document number 895, dated April 26, 2024.

Since there were no interventions involving patients in the context of this research, nor were any data used that could reveal patients’ private information to readers or other researchers, it was not necessary to obtain patient consent for the use of the data.

RESULTS

General Data

During the observed period, the EMS HCB conducted a total of 3,345 interventions in the field. Of that number, 1,501 were male (44.9%) and 1,801 were female (53.9%). Data on gender were missing for 41 patients (1.2%). Information on age was available for 3,285 patients (98.2%), while data were missing for 60 patients (1.8%). In total, 5,776 diagnoses were recorded, with an average of 1.7 diagnoses per patient.

Of the total number of patients, 175 (5.23%) were diagnosed with one or more types of cancer. In total, 209 diagnoses of malignant diseases were recorded, representing 3.62% of all diagnoses made by EMS HCB field teams during the observed period.

Age and Gender

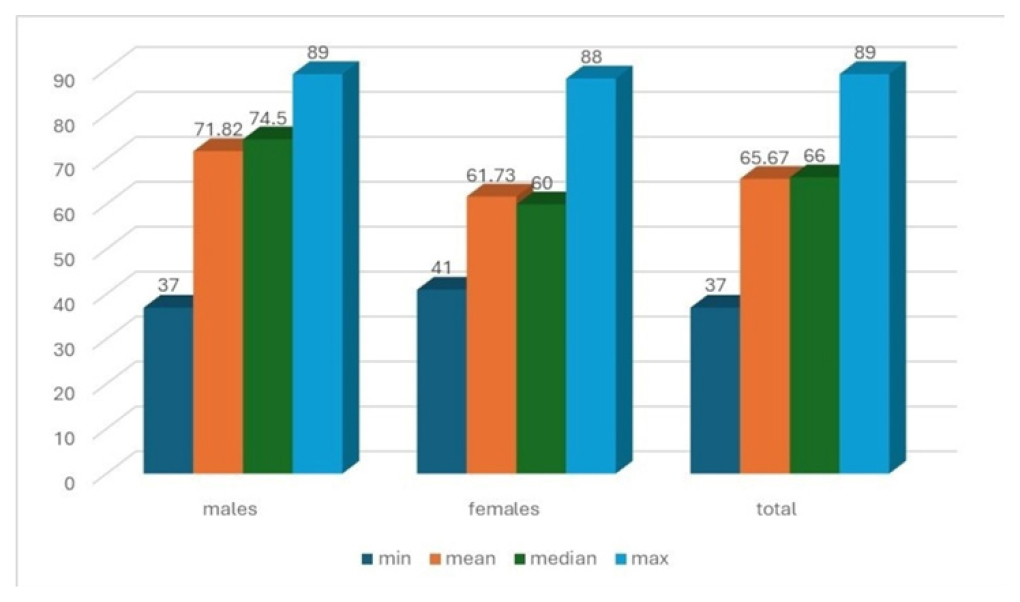

Among the patients diagnosed with cancer, 69 (39.4%) were male and 106 (60.6%) were female.

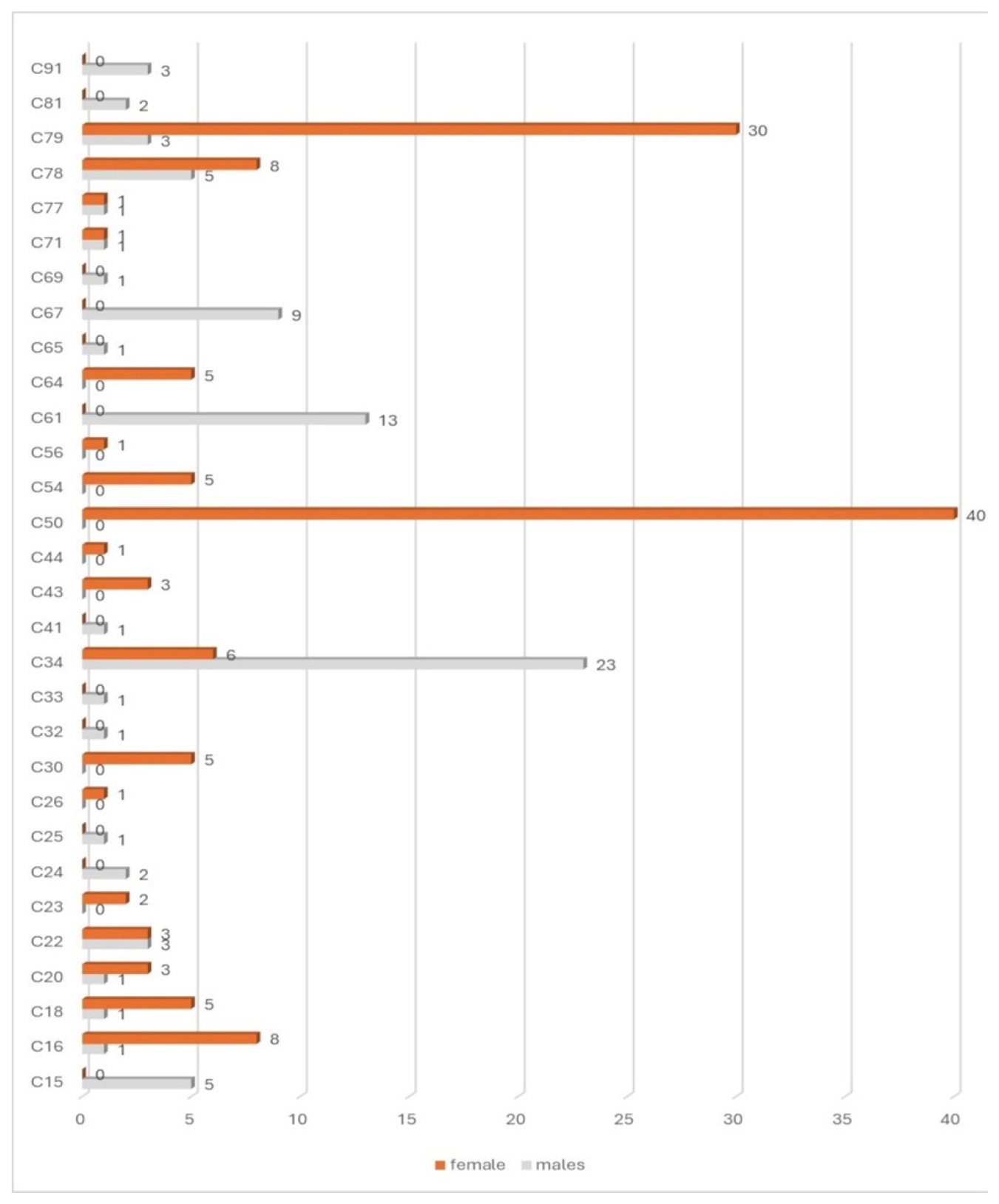

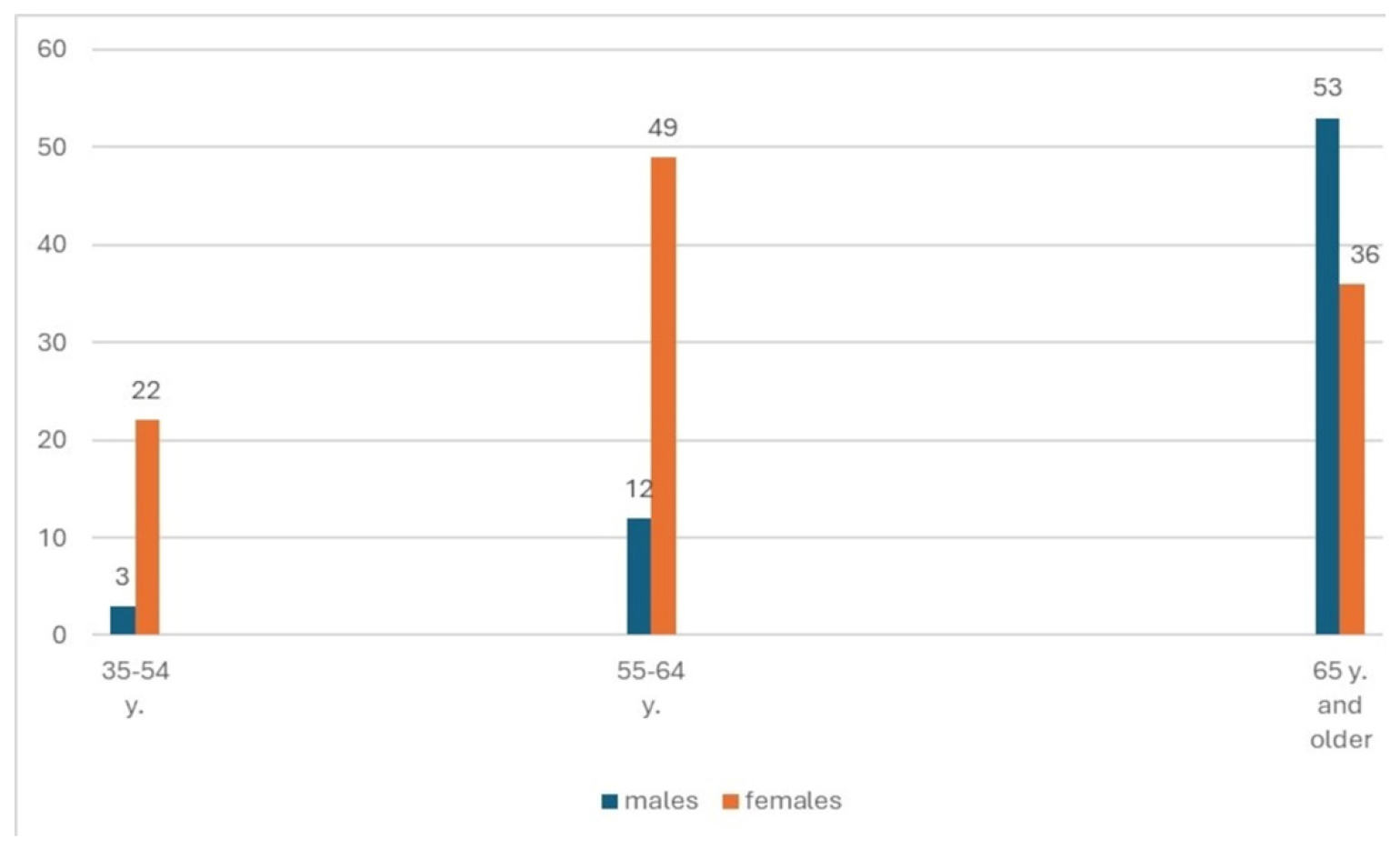

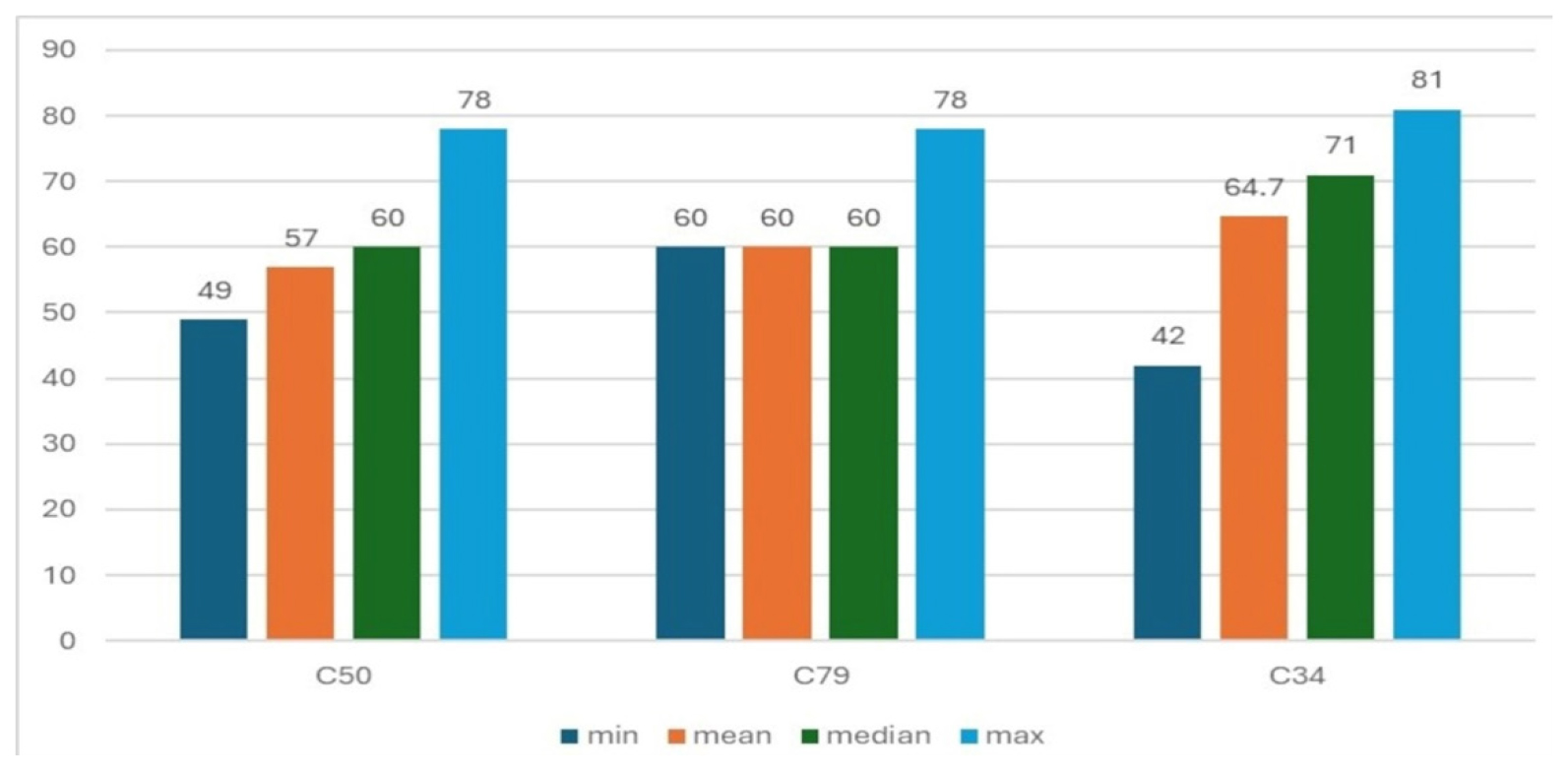

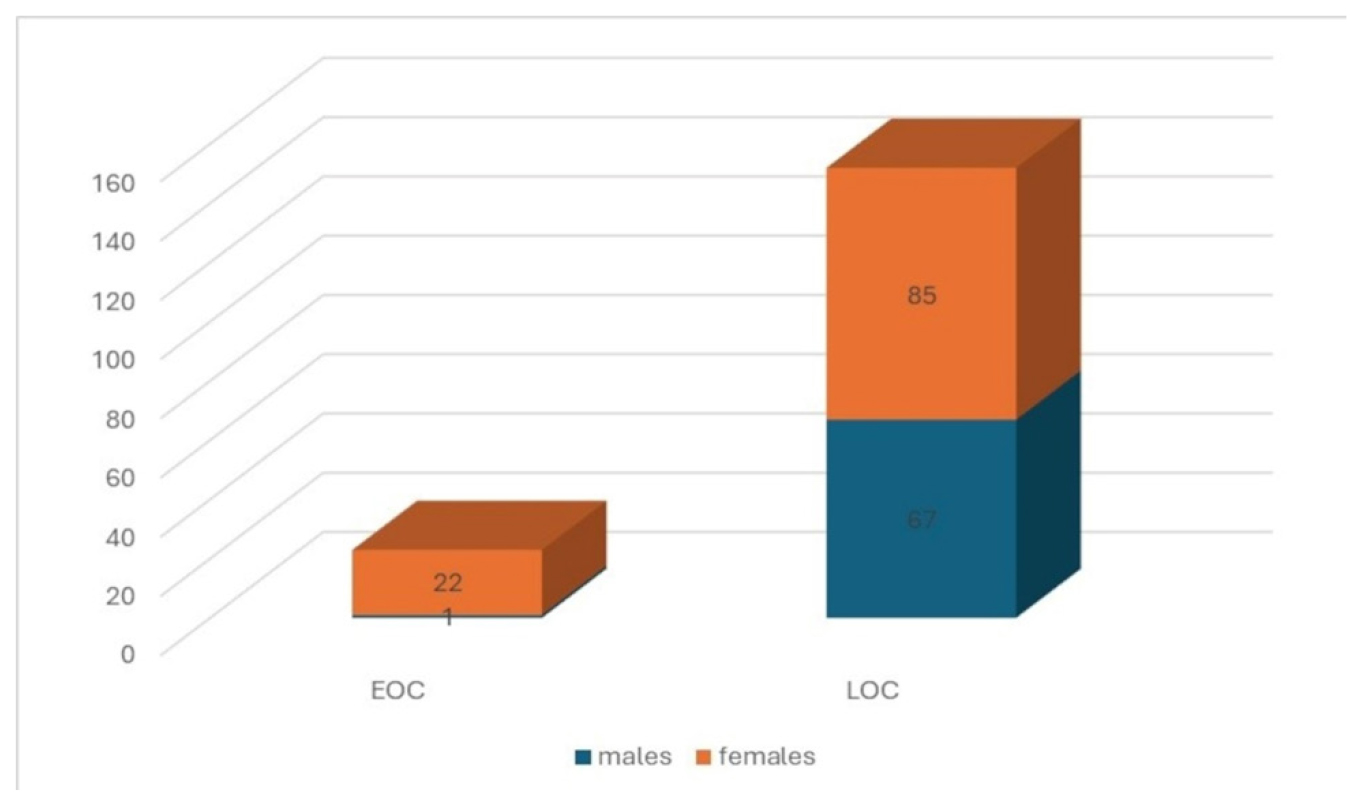

Figure 1 show the minimum, maximum, mean and median ages for all patients, which are also categorized according to gender. Figure 2 shows individual diagnoses with the absolute number of patients (interventions) categorized by gender. Figure 3 illustrates the frequency of malignant diseases across the age categories, excluding younger age groups where no malignant diseases were recorded. The age distribution of the most common malignancies is shown in Figure 4. Figure 5 depicts the ratio of EOC to LOC by gender, with the distribution being 13.14% for EOC and 86.86% for LOC.

Figure 1:

Age structure by gender.

Figure 2:

Total number of patients with malignant diseases, by individual diagnoses and gender.

Figure 3:

Distribution of diagnoses by age categories and gender.

Figure 4:

Age structure of patients with the most common malignant diseases.

Figure 5:

Ratio of EOC to LOC, by gender.

Therapy

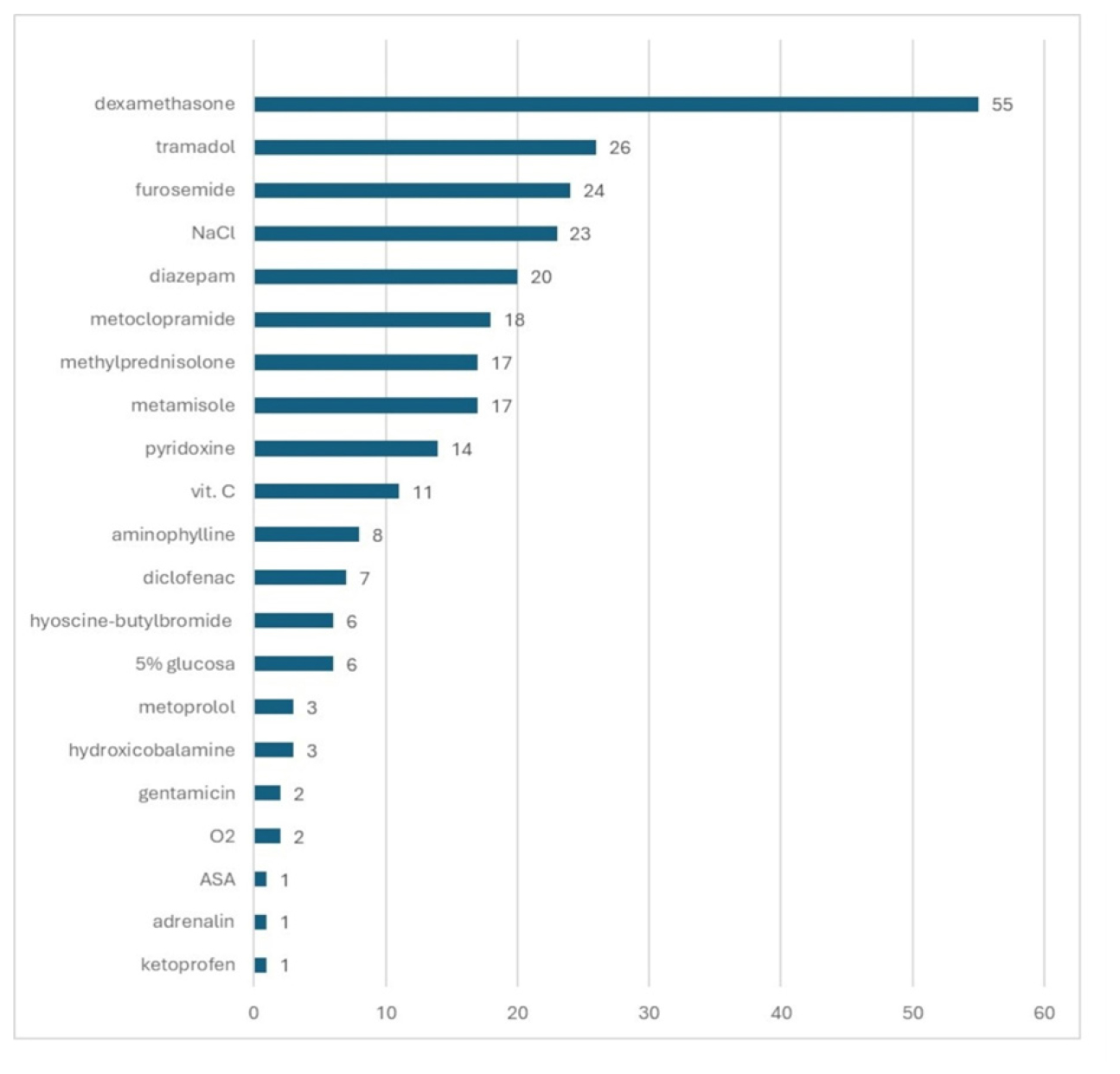

During interventions by the EMS HCB, 34 patients (19.43%) did not receive any treatment, one patient’s treatment was not relevant to the study and 140 patients (80%) received some form of treatment. The administered therapies are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6:

Administered therapy. ASA-Acetylsalicylic acid; vit. C-Vitamin C (ascorbic acid), NaCl-0.9% NaCl solution for intravenous use.

Of the 24 patients who received furosemide, nine had only a diagnosis of cancer. The remaining patients, in additional to cancer, also had the following diagnoses: three had hypertension, four edema, one had chronic kidney insufficiency and urinary retention, one had dyspnea and several cardiological diagnoses, one had COPD and soft tissue disease and one had fatigue and a combination of endocrinological diagnoses. Three patients received metoprolol intravenously. Of these, one patient did not have a diagnosis of a cardiac rhythm disorder, while the other two did (I47 and I48). It is unclear whether there was a clerical error in correctly specifying a diagnosis that would justify the use of diuretic therapy, or if there was another reason for the discrepancy between the diagnosis given and the prescribed therapy, as seen in aforementioned cases.

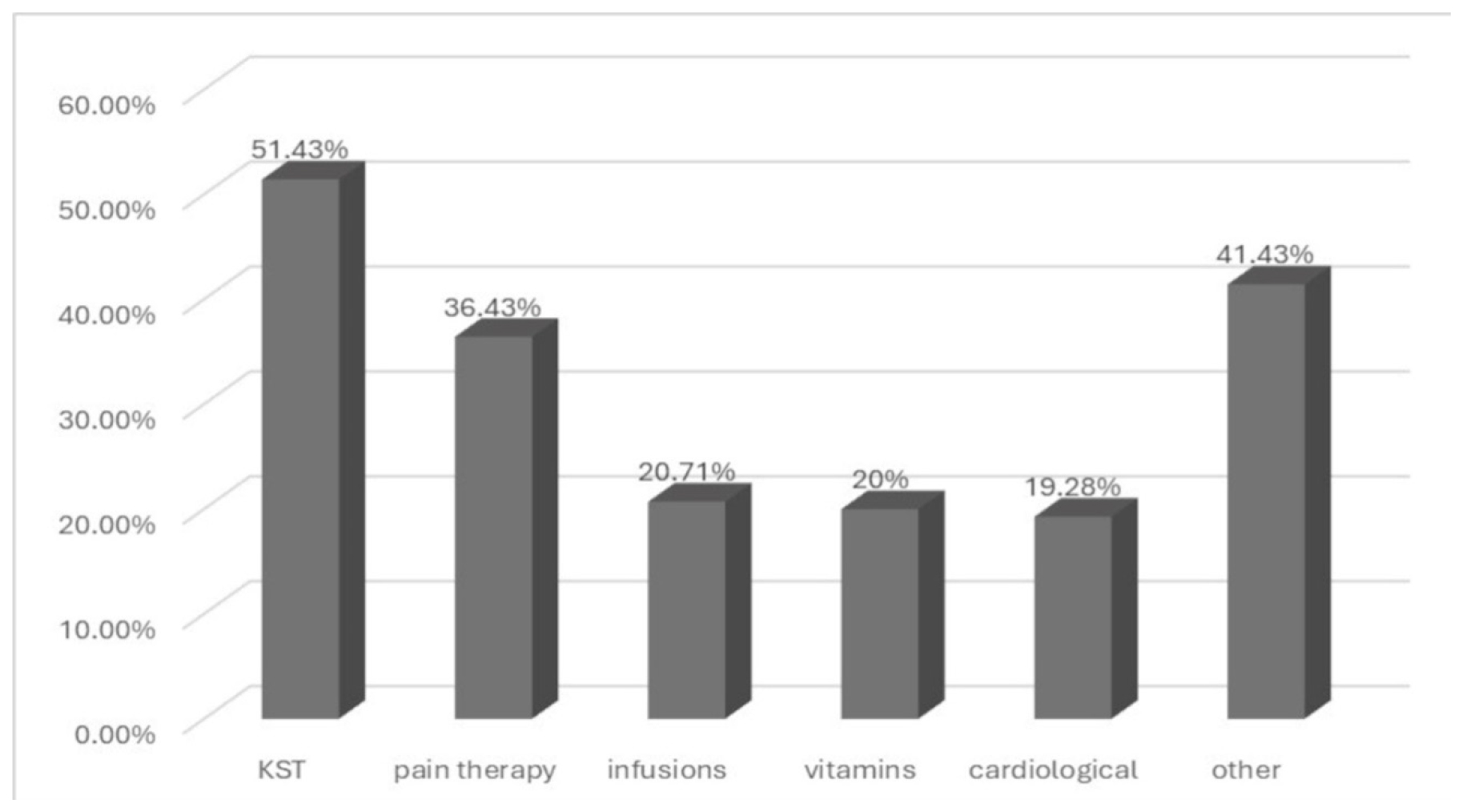

The most frequently prescribed combination therapy was tramadol and dexamethasone, administered in eight cases (4.6%). Figure 7 shows the percentage distribution of the administered therapeutic groups.

Figure 7:

Percentage share of individual therapeutic groups.

Referral of Patients

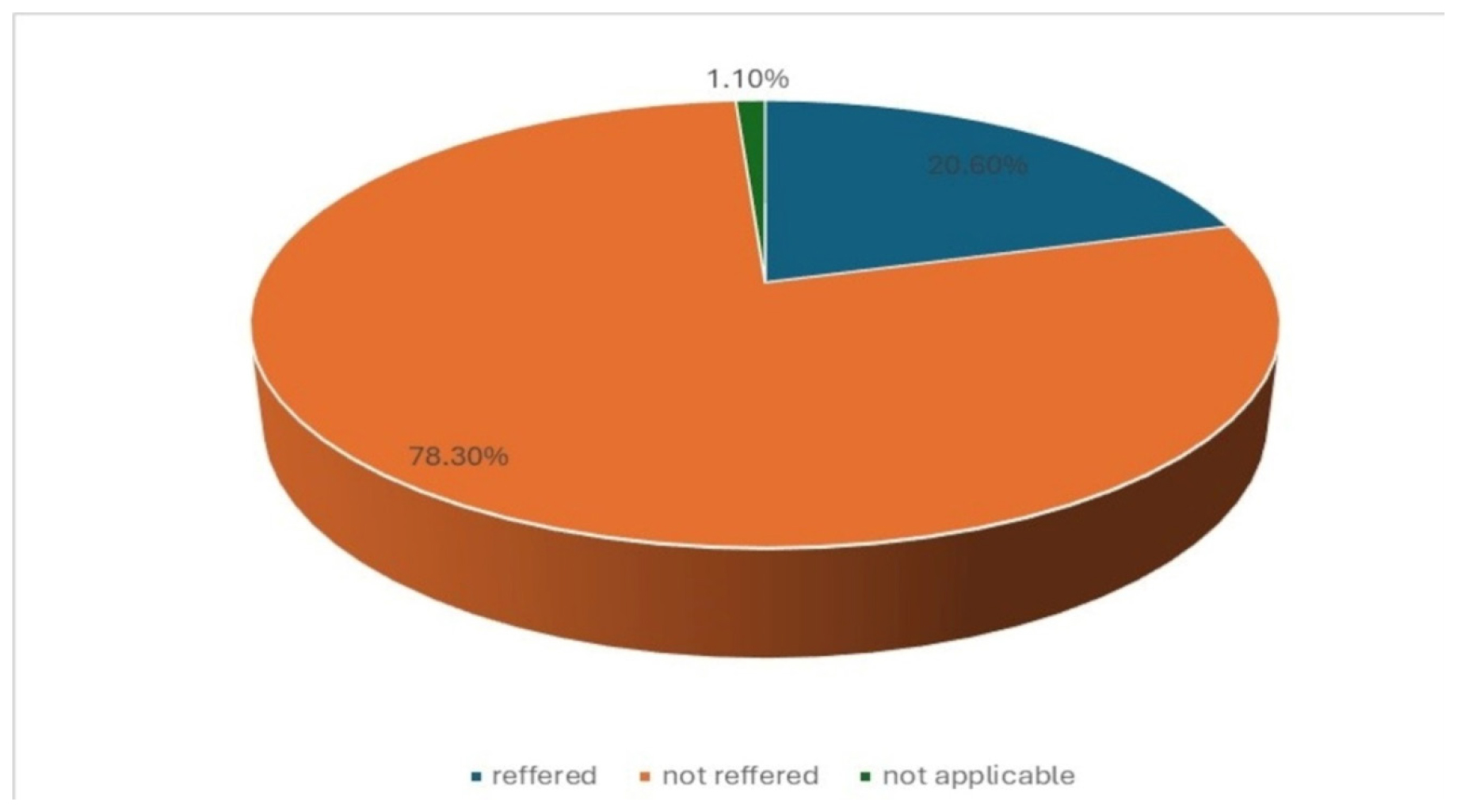

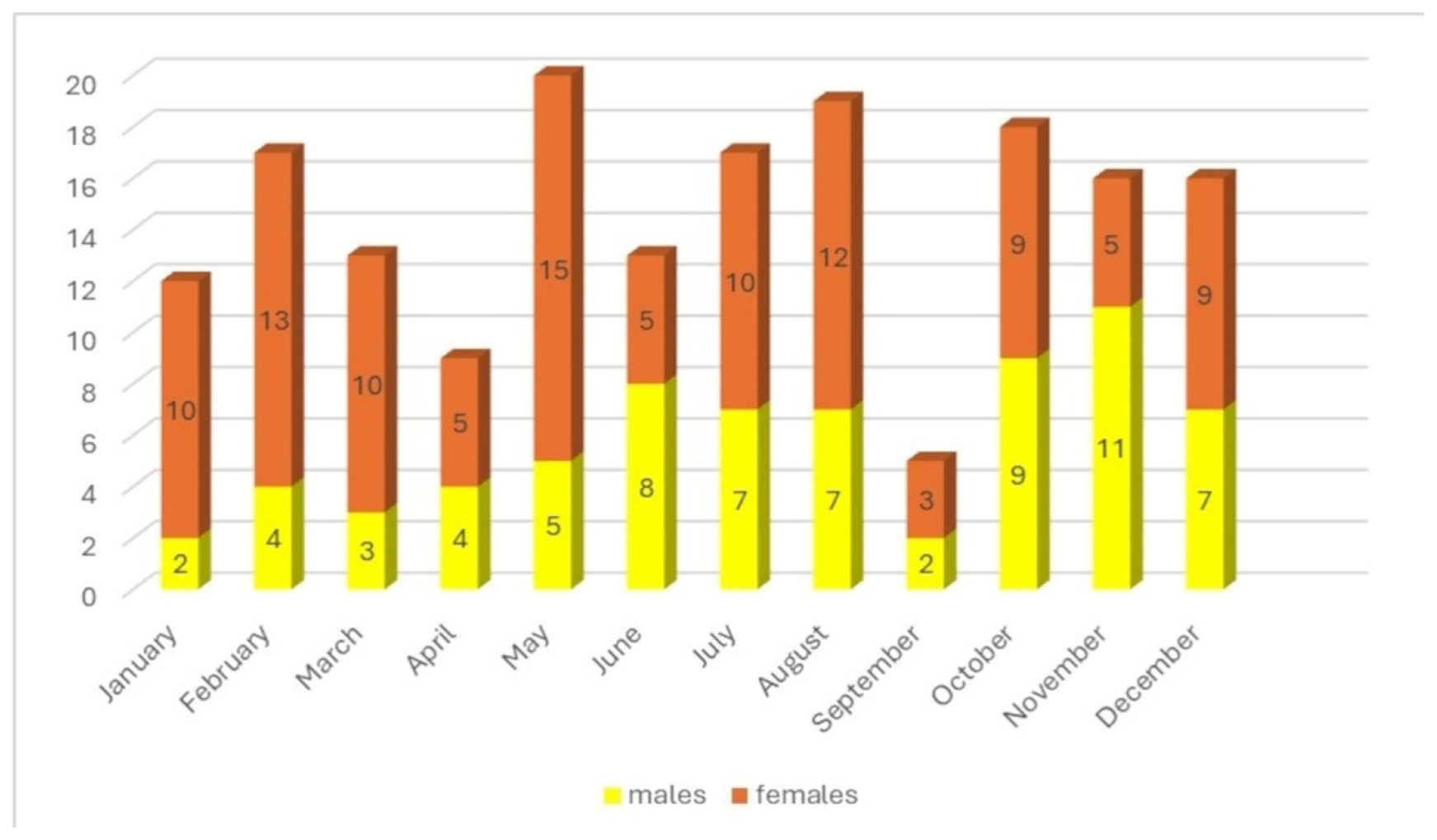

This paper also addresses the analysis of patient referrals to higher levels of the healthcare system. Patients are considered referred if an EMS HCB doctor, after an examination in the field, directed them to a higher level of healthcare-such as a hospital. Patients are not considered referred if an EMS doctor only recommended that they contact their general practitioner or undergo laboratory testing and/or radiological imaging within HCB. The ratio of refereed to non-referred patients is shown in Figure 8. Figure 9 presents a monthly breakdown of interventions for patients with cancer, categorized by gender.

Figure 8:

Referred and not referred patients.

Figure 9:

Distribution of interventions for patients with malignant diseases by month and gender.

DISCUSSION

In our study, there was a noticeable higher incidence of female patients among those referred by EMS HCB. A large study conducted in the USA by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also found a higher incidence of cancer in females.[11] However, other studies suggest a higher prevalence of male patients with cancer presenting to Emergency Departments (ED).[12] According to the WHO, there are more men suffering from various forms of cancers globally.[13] We believe that differences in gender distribution may vary at the national level and even at the level of smaller organizational units within institutions or districts within a country, due the varying distributions of malignant diseases within specific geographic areas, as well as population differences.

In our study, 5.23% of patients who contacted EMS HCB during the observation period had a malignant disease. According to data available in literature/research database, this percentage ranges from about 0.8%to as high as 9%.[14–20]

The age distribution in our study shows a higher mean and median age for male patients. Isikber and colleagues observed the same trend in their study, with the mean age for female patients being 57.5 y and 63.3 y for male patients.[21] According to Said and colleagues, the average age of oncology patients presenting to the ED was 53.7 y.[22] Malignant diseases are most common in the population aged 60 and older, according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI).[23] The same source reports that the median age at which cancer is diagnosed is 66 y. Although our study does not analyze patients’ age at the time of the diagnosis of cancer the median age for our patients with malignancies is also 66 y. Grewal and colleagues report the same median age.[24]

According to data from research databases, EOC is less common, accounting for about 22% of cases.[25] Current research also shows that EOC is more frequent in males.[26] The Institute of Public Health of Serbia reports that 9% of all malignancies found in men, in Serbia, are EOC, while the percentage is 15.6% in women respectively.[4] According to the same source, in Serbia, the mortality rate from malignant diseases in men under 50 years old is 31.5% of total number of deaths from cancer, whereas for women this percentage is 32%. The given data are from 2019, so an analysis for the period from 2020 onward is much needed.

The most prescribed therapy was corticosteroids. Our teams used dexamethasone and methylprednisolone. Pain medications were shown to be the second most frequently prescribed therapy. Literature data suggest that the most prescribed group of drugs for oncology patients in the ED is analgesics.[27] According to the same source, antiemetics were administered to 47.6% of patients with malignancies who presented to the ED. While corticosteroids play a key role in the treatment of oncology patients, they also come with a range of side effects, requiring caution in their use.[28] About one-fifth of the patients for whom EMS HCB intervened due to cancer and cancer-related illness were referred to a hospital for further examination and/or treatment. While this data is not directly comparable with the data found in literature, it might be somewhat analogous to hospital admissions in studies analyzing oncology patients’ presentation to emergency departments at hospitals. For instance, Legramante and colleagues found that over 70% of patients were admitted to hospital after an initial emergency department examination.[29] Similar findings have been reported by other researchers.[30]

The presentation of interventions by month attempts to establish an annual pattern; however this requires further long-term analysis.

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, it pertains to field teams, which in Serbia consist of a medical doctor-who may be either a general practitioner or a specialist-a medical technician and an ambulance driver. The study does not analyze oncology patient presentations to hospitals. Additionally, the presented results are based on a population of approximately 25,000 residents covered by HCB and its EMS, so the findings cannot be generalized to other parts of Belgrade and Serbia. Moreover, our sample is not representative, but we believe it may serve as a basis for further research and future comparisons of data in the field of Emergency Medical Care (EMC) for oncology patients. The organization of EMS HCB may also, at least partially, account for the limited applicability of the data obtained through this study. Lastly, another limitation is the small number of studies addressing this issue in Serbia.

CONCLUSION

The number of people living with cancer is increasing, leading to a greater demand for Emergency Medical Assistance (EMA) among oncology patients. A comprehensive analysis of oncology patients presenting to Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and hospital admission departments is essential for understanding patients’ needs and improving oncology healthcare, particularly in the segment of Emergency Medical Care (EMC). Increasing and improving the resources dedicated to oncology healthcare and Emergency Medical Assistance (EMA) is also of great importance. Enhancing palliative care-a vitally important part of every country’s healthcare system-and improving coordination between Emergency Medical Services (EMS), hospital Emergency Departments (ED) and palliative care services are also necessary steps. Only with such measures can oncology patients receive all the medical assistance they need at a quality level which would ensure, as much as possible, a life with the least amount of suffering.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer. Available from:

https://www.who.int/ news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer - Miljuš D. Malignant tumors and mortality in Serbia and Europe: a comparative analysis. 2021

- . Health Statistical Yearbook of Republic of Serbia 2018. 2019:422-42. Available from:

http://www.batut.org.rs/download/publikacije/pub2018.pdf - Institute for Public Health “Dr Milan Jovanović-Batut”. Malignant tumors in the Republic of Serbia. 2019 Available from:

https://www.batut.org.rs/download/publi kacije/maligniTumoriURepubliciSrbiji2019.pdf - National Cancer Institute (NCI). Cancer statistics. Available from:

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics - International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Global Cancer Observatory. Available from:

https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype - Klemencic S, Perkins J. Diagnosis and management of oncologic emergencies. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(2):316-22. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Colakovic N, Colakovic G. Diagnostic and therapy emergency conditions in cancer patients. SJ urg.med. HALO. 2018;24(2):126-37. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ribelles N, Pascual J, Galvez-Carvajal L, Ruiz-Medina S, Garcia-Corbacho J, Benitez JC, et al. Increasing annual cancer incidence in patients aged 20-49 years: a real-data study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2024;10:e2300363 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Ill-defined diseases. Available from:

https://platform.who.int/mortality/themes/theme-details/MDB/ill-defined-diseases - Gallaway MS, Idaikkadar N, Tai E. Emergency department visits among people with cancer: frequency, symptoms and characteristics. JACEP Open. 2021;2:e12438 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Isikber N, Korkmaz M, Coskun M. Evaluation of the frequency of patients with cancer presenting to an emergency department. REV ASSOC MED BRAS. 2020;66(10):1402-8. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global cancer burden growing amidst mounting need for services. Available from:

https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing–amidst-mounting-need-for-services - Gallaway MS, Idaikkadar N, Tai E. Emergency department visits among people with cancer: frequency, symptoms and characteristics. JACEP Open. 2021;2:e12438 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Sadik M. Attributes of cancer patients admitted to the emergency department in one year. World J Emerg Med. 2014;5(2):85-90. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AJ, Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #286. 2021 Available from:

www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb286-ED-Frequent-Conditions-2018.pdf

[CrossRef] | [Google Scholar] - Lee SY, Ro YS, Shin SD. Epidemiologic trends in cancer-related emergency department utilization in Korea from 2015 to 2019. Sci Rep. 2021;11:21981 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Grewal K, Krzyzanowska MK, McLeod S. Outcomes after emergency department use in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(3):E496-E505. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Majka ES, Trueger NS. Emergency department visits among patients with cancer in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2253797 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Gligorijević G, Simeunović S. Place of emergency medical assistance in the treatment of patients in the terminal stage of malignant disease. ABC-Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2002;2(3):33-5. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Isikber N, Korkmaz M, Coskun M. Evaluation of the frequency of patients with cancer presenting to an emergency department. REV ASSOC MED BRAS. 2020;66(10):1402-8. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Said N, Awad W, Abualoush Z. Emergency department visits among patients receiving systemic cancer treatment in the ambulatory setting. Emerg Cancer Care. 2023;2:6 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). Cancer risk by age. Available from

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age#:~:text=A%20similar%20pattern%20is%20seen,66%20years%20for%20prostate%20cancer - Grewal K, Krzyzanowska MK, McLeod S. Outcomes after emergency department use in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(3):E496-E505. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ribelles N, Pascual J, Galvez-Carvajal L, Ruiz-Medina S, Garcia-Corbacho J, Benitez JC, et al. Increasing annual cancer incidence in patients age 20-49 years: a real-data study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2024;10:e2300363 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Voeltz D, Baginski K, Hornberg C. Trends in incidence and mortality of early-onset cancer in Germany between 1999 and 2019. Eur J Epidemiol. 2024;39:827-37. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Caterino JM, Adler D, Durham DD. Analysis of diagnoses, symptoms, medications and admissions among patients with cancer presenting to emergency departments. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190979 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Aldea M, Orillard E, Mansi L. How to manage patients with corticosteroids in oncology in the era of immunotherapy?. Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:239-51. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Legramante M, Pellicori S, Magrini A. Cancer patient in the emergency department: a “nightmare” that might become a virtuous clinical pathway. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:6387-91. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef MJ, de Nijs E, Horeweg N. Palliative care needs of advanced cancer patients in the emergency department at the end of life: an observational cohort study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(3):1097-107. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]